SMOKE AND MIRRORS (CATALOG ESSAY BY KAREN MOSS)

During the past decade Mary Anna Pomonis has explored architecture and geometries associated with spirituality in her paintings and sculpture. For her solo exhibition, Iris Oculus, presented at the Lancaster Museum of Art and History in 2020, Pomonis installed her work in a transitional hallway ending with a tall, open doorway. Rather than fighting this awkward architecture, she made a totally integrated installation with vibrant, eight-sided geometric paintings hanging along the wall and two star-shaped sculptures suspended from the ceiling, one in the aperture of the large portal. This led the viewer along a proscribed pathway to an over-sized, eight-pointed star––like encountering a rose window at the end of a church nave or transept, reiterating the connection to spirituality of her work.

Pomonis’ choice of the number eight also refers to the 8-pointed temple rosette form of the goddess Inanna, the ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, beauty, war, and fertility. She weaves this elemental, female symbol within her own vibrant, geometric aesthetics. According to the artist, “Finding a feminist form at the beginning allowed me to extend myself in both temporal directions: into the history of feminine energy and the future of universal energy devoid of gendered identity.” Eight is also connected to the Ouroboros—the ancient symbol for infinity derived from the image of the snake eating its tail––used in cathedral domes and on skylights in other religious architecture. By using this number, Pomonis sets up a rule for producing her work as she underscores the idea of sacred geometries and spiritual spaces.

The Iris Oculus is a precursor to Pomonis’ new installation, Smoke and Mirrors, inspired by the temple poetry of Enheduanna that also celebrates the goddess Inannna. The title references the “magic” used by illusionists and artists alike to amplify light and transform a space. As Pomonis observed about Eastern Washington University gallery:

When I first saw the EWU gallery space, I was struck by the architecture and the feeling of spirituality in the building. Based on a 12-sided polygon, a dodecagon, it consists of walls that form a broken, spiral-like circle. On the second floor, a balcony leads from each classroom to architectural niches that enable intimate viewing from above. This creates the feeling of the art hovering in space above the stunning brickwork on the floor that from multiple perspectives appears to be a nautilus shell, echoing the spiral. The EWU gallery space presented me with the opportunity to highlight my work in what I feel is a utopian modernist and spiritual space where art itself is the deity worshipped.

Prior to the World’s Fair Expo in 1974, several students of Walter Gropius at Harvard School of Design came to work in Spokane, including architects in the firm McClure and Adkison who designed the EWU art building and gallery. Pomonis immediately recognized how the utopian, modern architecture of the space had great potential for her work. In her site-specific installation, she interjects her ideas about sacred geometry into her abstract paintings and the architecture to transform this highly idealized, modernist environment into a sacred space.

Initially, Pomonis envisioned the space as a ring of fire or a magic circle of blue flames, imagining herself in the center of a sacred geometric form, such as the pentagram. She wanted to evoke the geometry inherent in both magic diagrams and in historic architecture such as floating domes in Greek Orthodox churches. Pomonis finally settled on the hexagram for its association with spellcasting and the religion of Wicca.

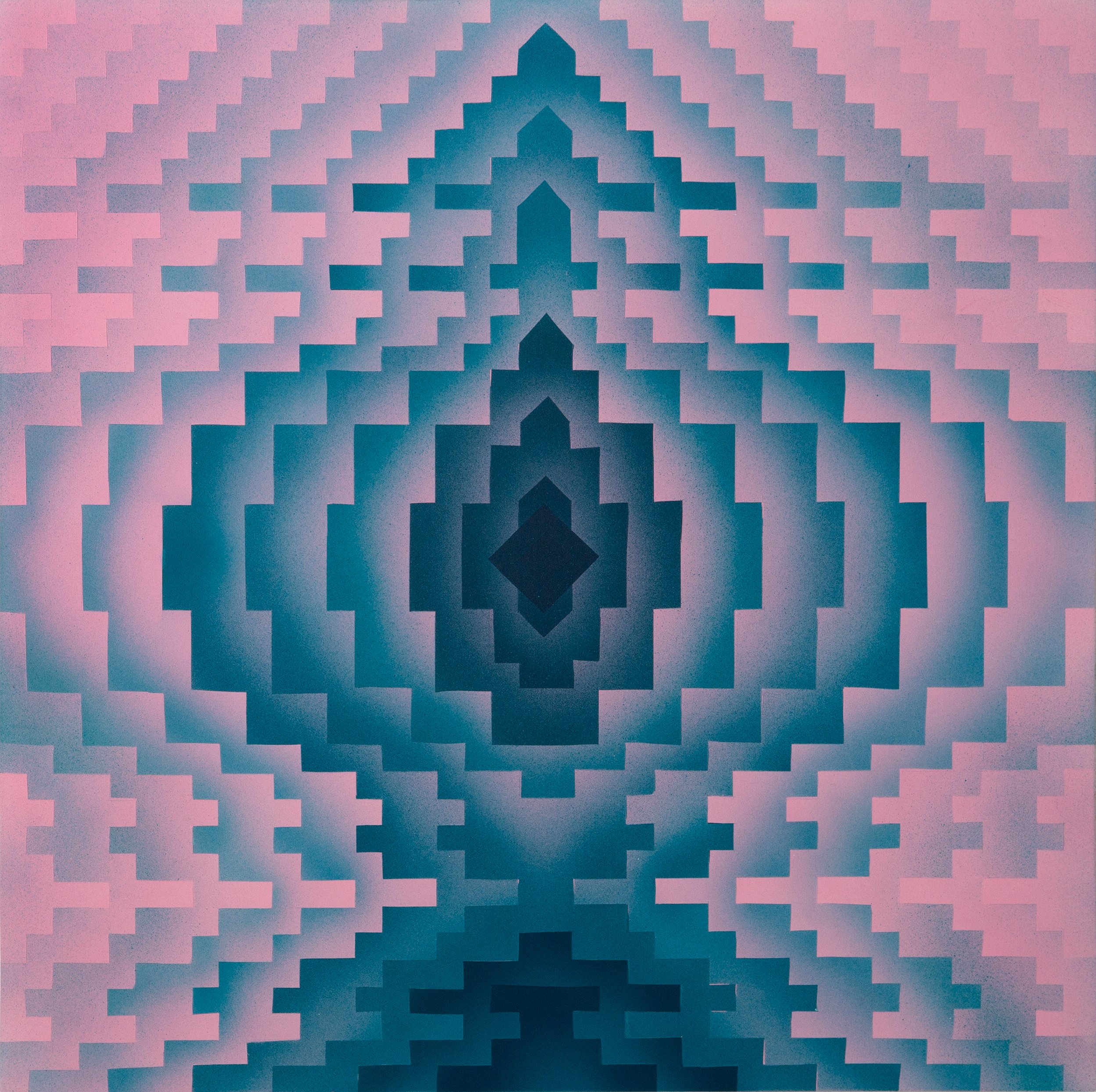

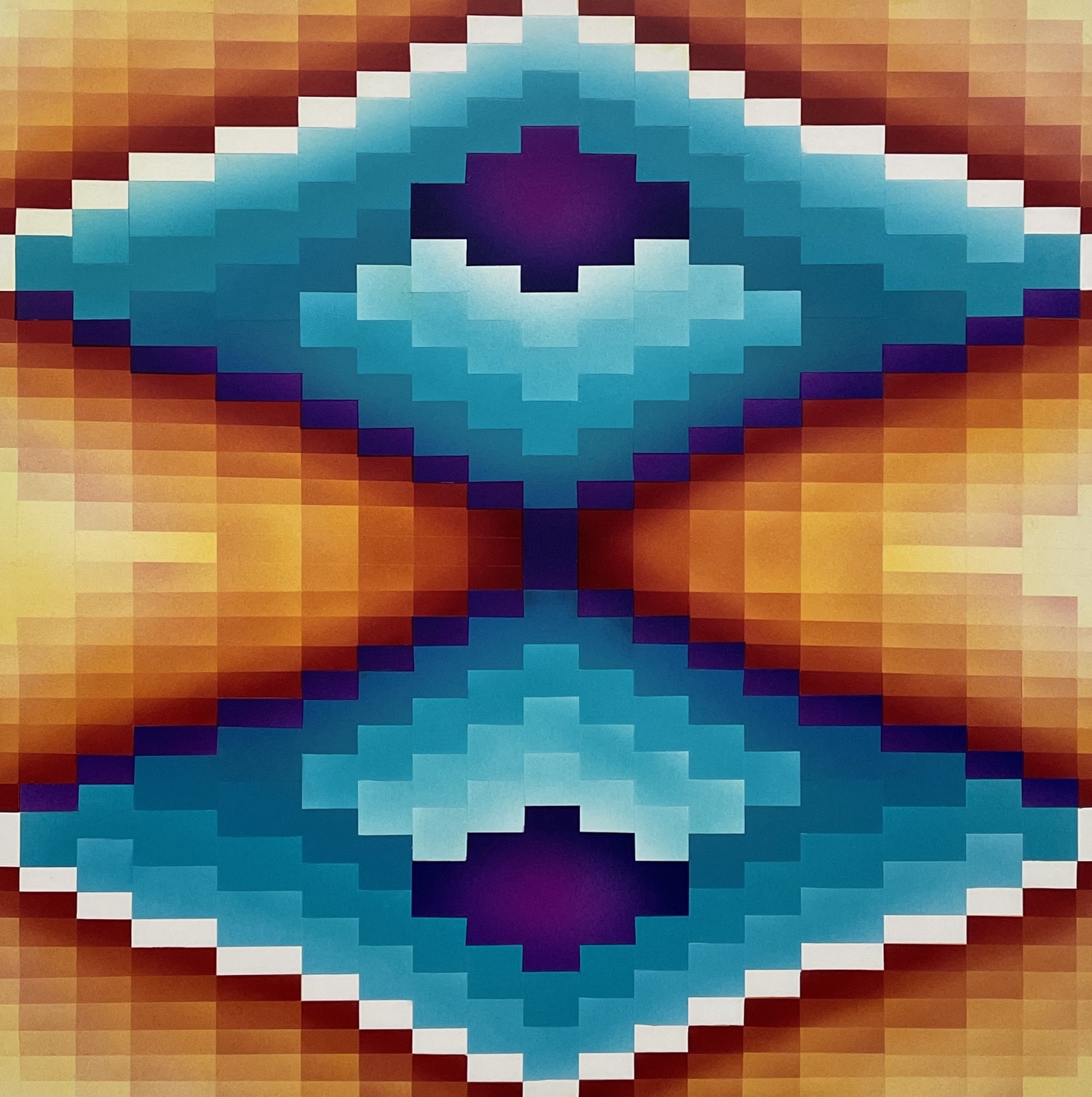

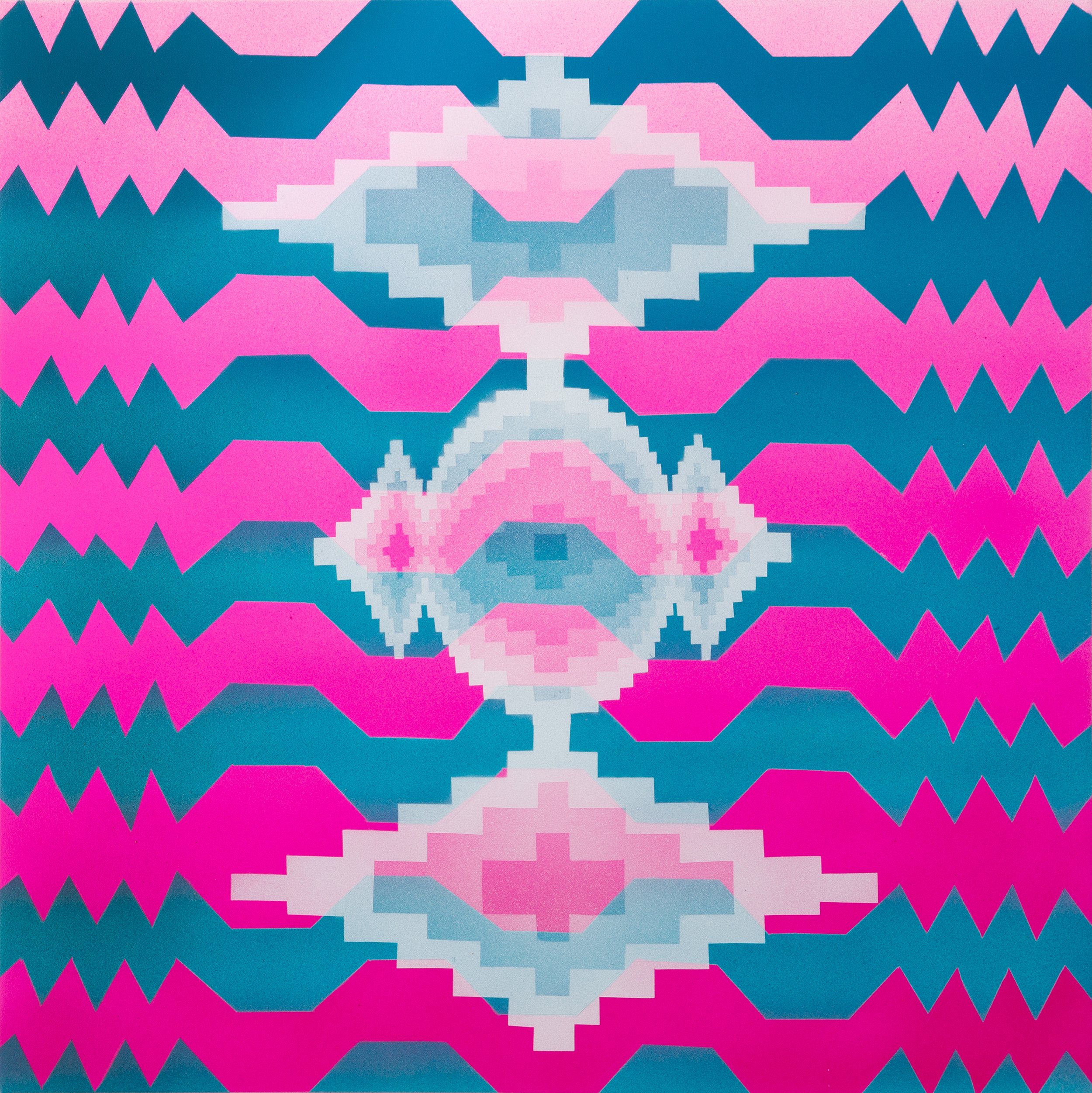

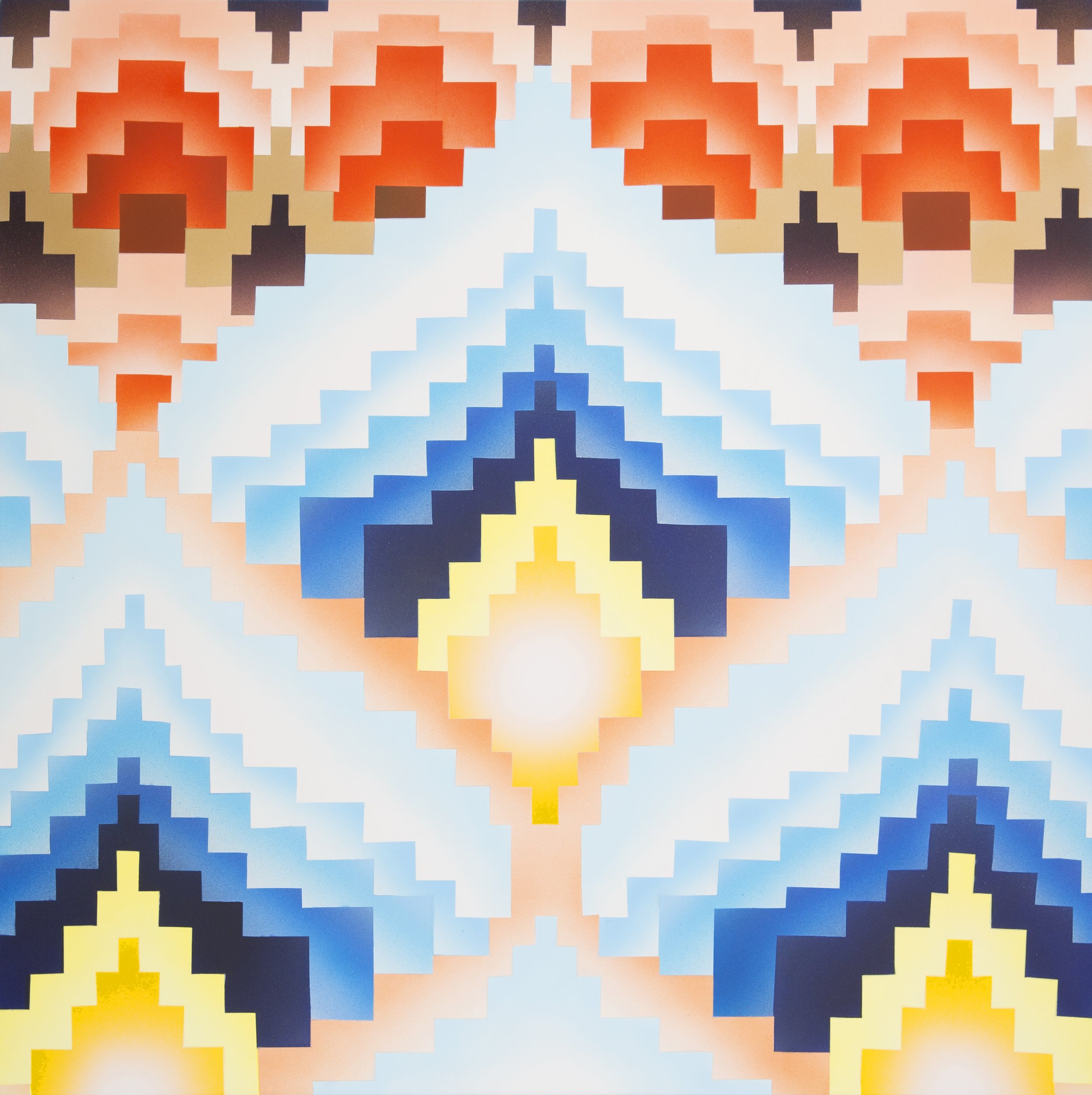

In Smoke and Mirrors Pomonis aims to amplify the light and geometry of the gallery by transforming it into a meditative, sacred space. Her twelve works are painted in air-brushed colors ranging from vivid, florescent hues to subtle pastels and warm bronzes. Some are geometric and others more organic and curvilinear, but all have a pulsating pattern with a strong central focal point. The geometric paintings and other objects in the gallery represent the five elements associated with the hexagram: water, air, fire, earth, and spirit.

Water is conveyed by mirrored reflection and stereoscopic symmetry in zig-zagged patterns with a rippling effect. Fire is seen in the bargello flame patterns derived from Missoni textiles and warm, metallic bronze finishes that reflect spiritual illumination. Air is literally used to make the paintings: Pomonis’s meticulous air-brushing creates colors that vibrate and oscillate into auras that reference a transcendence that recalls paintings of the ascension of Christ or the abstract, modern works of the Transcendental Painting Group. The element of earth is most evident in the brickwork of the gallery: the intricate pattern mirrors the geometric ceiling and skylights, while the triangles in the floor directly align with triangles or negative space and light in the ceiling. Finally, spirit: Pomonis’s use of reticella lace hand-made by Mariettta, her departed grandmother, materially and spiritually evokes her memory.

These five elements connect as they transform the exhibition into an active hexagram: the viewer enters the gallery as a portal into an elevated consciousness. In the center is a tent-like sculpture constructed from smoky Plexiglas with hexagonal and square cut outs, which Pomonis covered with her grandmother’s reticella lace to create light-filtered portals. Visitors can enter the tent, sit on a stool, and meditate on both the works of art and the architecture. Mirrors on the interior reflect the lace-filtered exterior, conflating inside with outside, and personal interiority with public exteriority. Inspired by ancestor worship inherent in traditions of healers and priestesses from the Hiereiai of Greece to the Curanderas of Mexico, Pomonis designed these portals to evoke the magic and mystery of communication with the dead or our own internal communications with the memories of our ancestors.

In Smoke and Mirrors Pomonis integrates her art-making, feminism, and spiritual practice to transform the modernist architecture of the EWU gallery. Using colors and patterns in her paintings that reflect the gallery’s earthen clay brick floor and the mirrored light skylights of its ceiling, the artist engages this entire context of this extraordinary space making a wholly integrated installation. Ultimately, she strives to create the euphoric feeling of an embodied, spiritual experience, which is indeed magical.

-KAREN MOSS

BIOGRAPHY

Karen Moss is a Los Angeles-based art historian, independent curator, educator and writer whose areas of expertise include conceptual and performance art since the 1960s, contemporary art and social practices, and experimental education. Moss is retired Professor of Critical Studies and Director of the MA Curatorial Program at USC Roski School of Art and Design. She holds a BA in art history and studio art from UC Santa Cruz and received her MA and PhD degrees in art history from USC.

Moss has organized exhibitions, artist residencies, symposia and public art projects nationally and internationally for more than 30 years. She held senior-level curatorial positions at Orange County Museum of Art; San Francisco Art Institute; Santa Monica Museum of Art, and Walker Art Center. Earlier in her career she worked as at MoCA, Los Angeles, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum, after she was a curatorial fellow in the Whitney’s Independent Study Program.

Moss’ current curatorial project is the first retrospective of intermedia artist Alison Knowles––the last living and only female core member of Fluxus––that premiered at the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive in 2022 then tour to other US venues and Europe in in 2023-25. Previously, she was consulting curator for Talking to Action, part of the Getty’s PST LA/LA that was premiered at Otis College of Art and Design (2018) then toured nationally. For the previous Getty’s PS /Los Angeles, she co-curated State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970 that opened at Orange County Museum of Art (2012), then toured the US and Canada.

Moss has taught undergraduate and graduate art history, critical theory and curatorial studies at California State University, Long Beach, Otis College of Art and Design, San Francisco Art Institute, University of Minnesota, and University of Southern California. She is a frequent guest lecturer at museums, art schools, and universities and has authored numerous museum exhibition catalogues, guest essays for arts publications, and article for scholarly journals.

MARY ANNA POMONIS: INTO HER (CATALOG ESSAY BY ANNIE WHARTON)

peg my vulva

my star‐sketched horn of the Dipper

moor my slender boat of heaven

my new moon crescent beauty

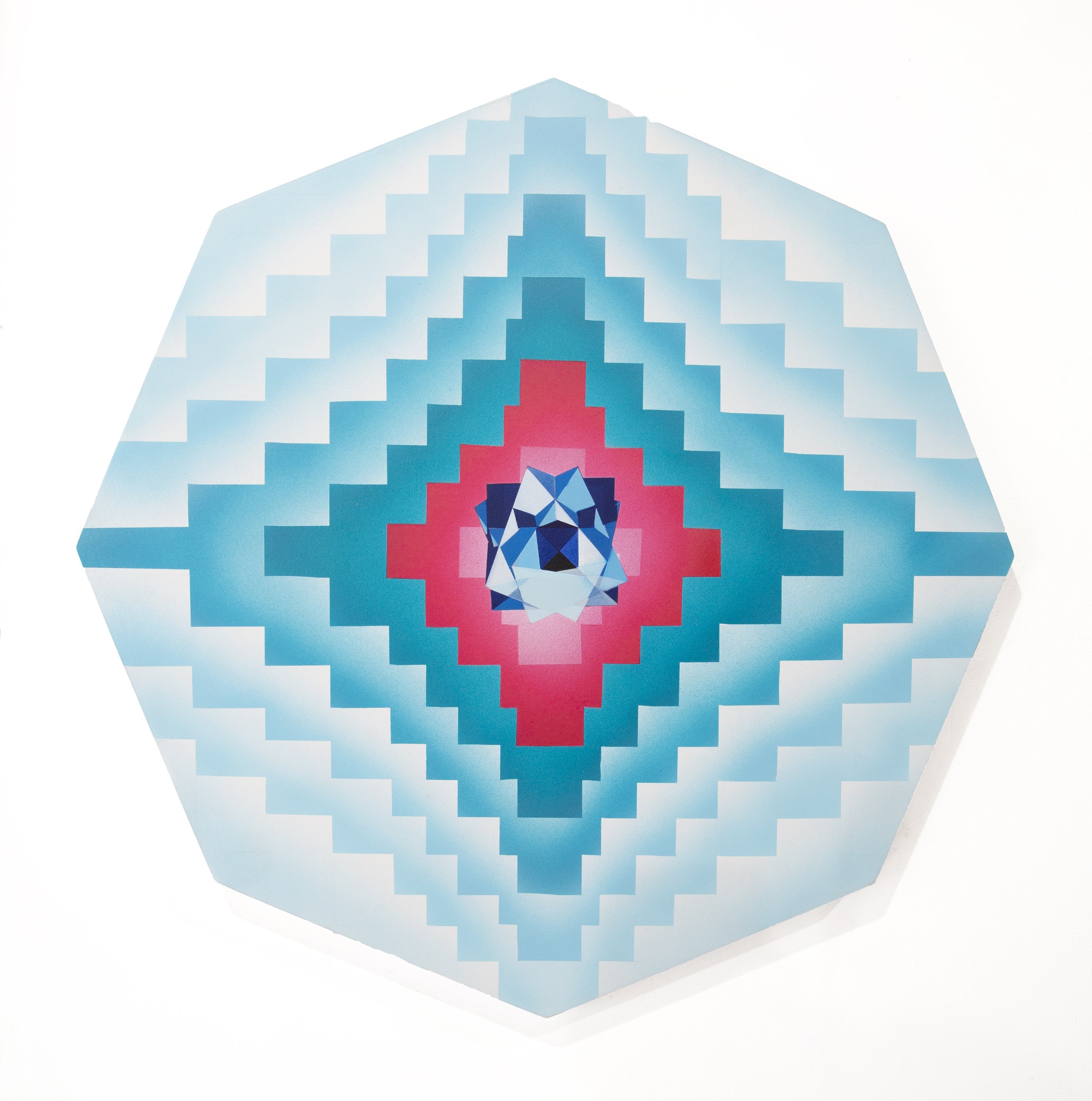

So goes the Sumerian temple poem exalting Inanna, Mesopotamian goddess of war and sex. This ancient work was composed by Enheduanna, a woman, whose name has been recorded as the first known composer of poetry in any written language.(1) The symbol of Inanna is an 8-point star, which recurs in ancient Sumerian bas-reliefs and Byzantine coins and flags.(2) In the exhibition titled Into Her, Mary Anna Pomonis has created her own powerful series of visual poetry to honor Inanna. Each two-dimensional painting exquisitely renders spaces both three-dimensional and temporal and is made up of repeated cryptic formal rhythms that engage mathematical codes and channel forces beyond human comprehension.

In a world that is increasingly more uncertain, artists have a palpable need to produce art that is otherworldly. In a conjuring act, Pomonis summons her own power as a woman and, further, as an artist. Via the masochistic endeavor of measuring and graphing, taping and masking, spraying and calibrating, supernatural concepts augmented by her rigorous production include ideas that exist beyond the laws of this earth. While women have generated art as a spiritual endeavor for eons, in more recent art history, this tradition has been observed in the work of Hilma af Klint, who produced geometric paintings that are some of the earliest metaphysical manifestations of 20th-century abstract art. Emma Kunz divined Modernist mandala forms using a pendulum to create large drawings as part of her practice as a healer, and Agnes Martin made obsessively organized contemporary art grids that concretized her statement “everything, everything is about feeling.”(3)

Into Her illustrates Pomonis’ airbrush dexterity as a sensitive and scholarly practice, simultaneously honoring and distancing herself from the process seen in Los Angeles’ ubiquitous car culture. Airbrush, often relegated to the masculine realm of gadget-fetish, has been stripped of its gendered identity. Much like motors or guns, the moving parts of the “male” apparatus are gear-laden, requiring compulsive cleaning, and are of a form quite the opposite of intuition or feeling. Pomonis has practiced the craft to such a degree that she can deftly wield the contraption to produce both crisp lines and dreamy fades. The sumptuous backgrounds of her paintings have an ethereal quality like ‘70s blended silkscreen posters. And the geometry of her polyhedra is dramatically more complex than the cubes or spheres of quotidian life.

Plutarch attributed the saying “God geometrizes continually” to Plato,(4) and sacred geometry can be found in rock circles at Stonehenge, pyramids, Mayan temples, cathedrals of the Baroque, and the Parthenon. Even Le Corbusier used spiritual axioms to delineate his architecture.(5) Throughout her artistic career, Pomonis has synthesized systems derived from art, architecture, and naturally occurring geometric patterns such as crystals, beehives, stars, and diamonds. When asked about her practice, she reifies her connection to the divine, stating, “I allowed the 8-pointed temple Rosette form to guide me on my drawn investigation, and through this process of repeating and building, a spiritual energy is created and a certain power is harnessed. It is via this repetition that the space between the self and the universe is eliminated. I felt I was delving into an elemental feminist symbol, weaving my own aesthetic into a form that was beyond the particularity of myself, one that submerged the self into the symbolic and universal.”

This is an exercise in becoming, of meditation and deference to a mysticism remote, where the vibrational energy of 8-pointed crystal forms, endowed the narrative plane of Inanna’s descent, transmutes ritual math. Pomonis is accessing, unlocking, and awakening through a ritualistic process the imprint of a transcendent movement, rendered and animated of a phenomenal and historical equation that is in becoming realized through the work. It is this process through the spatiotemporal strata of a mythic and horological narrative experience that reveals Pomonis emerging from her dive into the depths, having retrieved a poetic sublime which vibrates as lines and matrices in airbrushed chartings of a way continually forward. The works of Into Her are new relics, recording her dimensional pilgrimage guided by the principles of a sacred geometry.

-- Annie Wharton

...

1. Meador, Betty De Shong, translator. “Sappho and Enheduanna”. By Enheduanna. Presented by Meador, Betty De Shong. Ancient Greece/Modern Psyche: Petros M. Nomikos Foundation, Santorini, Greece, 2009.

2. Black, Jeremy A., Anthony Green, and Tessa Rickards. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. University of Texas, 1992.

3. Agnes Martin, quoted in Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield, Agnes Martin Chicago: School of the Art Institute of Chicago Video Data Bank, 1976). VHS. Also see John Gruen, “Agnes Martin: ‘Everything, Everything is about Feeling… Feeling and Recognition,’ “ ARTnews 75, no. 7 (September 1976): 91.

4. Plutarch, “Convivialium disputationum,” liber 8,2.

5. Pennick, Nigel. Sacred Geometry: Symbolism and Purpose in Religious Structures. Harper & Row. (Library of Spiritual Wisdom), 1982.

MARY ANNA POMONIS: IN BRIO (CATALOG ESSAY BY DR. CHARLOTTE EYERMAN)

Adamant:

Mary Anna Pomonis, In Brio

(Catalog Essay) Like crafting a gem from an earthy hunk of stone, the painter transforms her materials, reinventing according to a finely honed set of technical skills, deep knowledge of traditions, and a singular vision. This new body of work, presented in the exhibition, In Brio, expresses Painter Mary Anna Pomonis' tenacious engagement with invention and convention, reconciling contradictory themes that inform her practice: strength and fragility, toughness and delicacy, transparency and opacity. Her primary subjects-- diamonds and gemstones--are so deceptively straightforward, so seemingly familiar, that at first glance one may be more struck by the stunning visual beauty of these paintings that belies their intellectual rigor.

Pomonis mines her subject informed by an encyclopedic fascination with contemporary and traditional art history, literary and art theory, popular culture, and ancient mythology. Current political and economic crises notwithstanding, she wears her Greek heritage with pride, and one senses the aptness of her Greek surname and its etymological link to Pomona, Greek goddess of abundance. The big dramas of ancient mythology capture her imagination, clashes between gods and mortals, men and women, battles resulting from hubris, that perennial human failing. Built into Pomonis’ sumptuous images of gemstones are embedded associations with riches, fame, love, and conflict. To produce these meticulous works, she brings an adamant focus to the physical, intellectual, and conceptual elements of making paintings.

The diamonds and emeralds Pomonis represents are gathered from images reproduced in books, magazines, advertisements and in a sense are descended from Pop Art: what soup cans and Marilyn Monroe were to Andy Warhol, celebrity gemstones are to Mary Anna Pomonis. She selects stones that are famous in their own right, as well as those owned and worn by celebrity owners, such as Elizabeth Taylor, whose legacy as a keen collector of jewelry lives on (a major auction of her collection will occur in December 2011).

Pomonis’ painting, When I Look Into My Ring It Gives Me the Strangest Feeling For Beauty after Elizabeth Taylor on the Krupp Diamond is at once a geometric abstraction, reading almost as an architectural space, as well as a synthesis of traditional genres. On one level, it’s a portrait (the of the diamond itself and as a metaphor of its famous owner, replete with the history of her tempestuous relationship with Richard Burton). As an investigation of an object, it recalls the great traditions of still life painting, particularly those produced in 17th-century Holland during its “Golden Age” of military and economic dominance. Then, painters created exalted images of luxury items in juxtaposition with fruits, flowers, and insects, serving as emblems of national pride and warnings about mortality, hubris, and the passing of time. Ironically, of course, Dutch predominance gave way to economic collapse and military defeat, the living passed on, as all do, yet the paintings endure, insistently reminding us of our own ephemerality.

The adamant, unyielding quality of Pomonis’ paintings and her practice strikes me, as an art historian equally engaged with contemporary art and the art of the past. Intriguingly, the words “adamant” and “diamond” both derive from the Greek word αδαμας (adamastos, "untameable,”) and refer to an exceptionally hard substance. In content and form, Pomonis explores the many facets of hardness: hard edges, hard substances, hard surfaces.

Within that hardness, though, are spatial, conceptual, and narrative openings. The gemstones are rendered with illusionistic skill, as well as a level of craftsmanship that acknowledges the role of the artist’s hand, eye, and mind. In some of her recent works, the openings are literal, as she has embarked, with a scientist’s caution, on an experimental path with cutting the canvases, particularly in those works that employ the chevron or diamond-shape (á la Mondrian, or 17th-century Dutch emblems in Protestant churches recorded in paintings by Saenredam). Pomonis’ works are literally multi-faceted, visually and thematically, as she slyly and subtly invokes our tabloid-obsessed fascination with famous actresses and their high-profile marriages and divorces.

The stars of the paintings are Liz Taylor and Jennifer Lopez, Hollywood Venuses, represented by their jewels, which shine on triumphantly regardless of their Olympian struggles in love. The rocks are hard, but the ladies are equally tough and beautiful and in this body of work, Pomonis celebrates strength, autonomy, and resurgence. Not incidentally, her own experience with marriage, motherhood, and divorce are inextricably linked to her seriousness and commitment as an artist.

Over the course of many years, Pomonis has developed techniques and materials that maximize her ability to render images that achieve a supreme flatness, with flawless surfaces. She mixes her own grounds and paints and uses industrial cup-gun sprayers rather than paintbrushes, a nod to her enthusiasm and reverence for Los Angeles artists in the California “Finish Fetish” vein, notably Billy Al Bengston and Judy Chicago and their canonical works from the 1960s and 70s. These two living artists are particular heroes for Pomonis, and are featured in many of the “Pacific Standard Time” exhibitions presently on view in Los Angeles. Those early works by Bengston and Chicago share a kind of LA-car culture DNA. For Pomonis, they emblemize the yin-yang of her fascination with masculine and feminine power, past and present.

Nothing about Pomonis’ paintings feels derivative or “influenced” by other artists (and they are paradigmatic opposites of the recent gem-inflected work of the stratospherically-hyped Damien Hirst). Rather, they are her singular contribution to a centuries-old tradition of painting. Her mode of investigation is subtle, multi-faceted, confident, evolving. In the world of her studio, one images that the prevailing goddess is Athena: wise, strategic, and strong.

--Charlotte Eyerman

Charlotte N. Eyerman, Ph.D. is a Los Angeles-based art historian, curator, and consultant. She has taught, lectured, and published extensively on subjects ranging from modern and contemporary art, film, and art history since the Renaissance. Eyerman has held curatorial positions at the Getty Museum, the Saint Louis Art Museum, and most recently guest-curated a “Pacific Standard Time” exhibition, Artistic Evolution, for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (through 15 January 2012).